2021 Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement: Highlights from a ‘Tough Love’ Budget

Danita Hingston

Thursday, 18 November 2021

On Thursday, 11 November 2021, South Africa’s Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana delivered his first Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS). The MTBPS gives government the opportunity to make changes and adjust the priorities identified in the February budget. It further serves to update the public on spending and provides an overview of the economic landscape. Most importantly, by detailing the government’s priorities for the next three years, the MTPBS (at least in part) fulfils the principles of fiscal transparency provided for in section 216 of the Constitution. The budget information presented in the MTBPS and Adjusted Estimates of National Expenditure (AENE) is especially vital for informing legislative debate and oversight.

Like most nations, South Africa was not spared from the devastating socio-economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, the third wave of the pandemic earlier this year and public unrest in July weakened economic recovery efforts. According to the South African Property Owners Association (SAPOA), the damage cost of the unrest is estimated to exceed R20 billion in KwaZulu-Natal while the overall impact on the national GDP will be R50 billion. Between 8% and 9 % of the country’s shopping centres were affected by looting and the cost of rebuilding is estimated at R14 billion. Further, around 40 trucks, which are estimated to be worth R500 million were set alight on the N2 and N3 highways.

Throughout the month of October, state-owned power utility, ESKOM implemented load-shedding across the country which adversely impacted economic productivity and exacerbated the strain on public finances. The most recent labour statistics indicate that the unemployment rate is at 34.4%. In addition, 55% of the population is living below the upper-bound poverty line (R1335) while 25% are experiencing food poverty (R624) . Researchers highlight that without the introduction of the COVID-19 grant at the beginning of the pandemic – the incidence of poverty would have been over 5% higher among the most vulnerable households and household income inequality would have been 1.3% to 6.3% higher. This illustrates the importance of timely social assistance measures in the face of crippling poverty and inequality.

On 10 November 2021, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) responded to South Africa’s most recent report on the government’s steps to implement the recommendations of the CESCR’s strengthening the for the realisation of socio and economic and cultural rights. The recommendations included, amongst others, ensuring that those with no or little income between the ages of 18 and 59 have access to social assistance. The Committee concludes that South Africa has made insufficient progress.

It was against this backdrop that Minister Godongwana delivered his speech.Key questions from millions of South Africans and civil society include whether the R350 Covid-19 relief grant would be reinstated? How will the government respond to the spiralling high unemployment rate? How will the government find funds to procure more vaccines? And pehaps most pertiently – would the MTBPS signal a more social just or ‘pro-poor’ fiscal response over years to come? In his speech, Godongwana quipped that he’d been asked by a journalist whether the budget was pro-poor and he responded that it was indeed ‘pro-poor’.

The key priority emphasised in the speech was the need for economic reconstruction through investment, job creation and debt stabilisation. The Minister also commented that the decision to continue (or discontinue) the COVID-19 grant lies not within Treasury’s jurisdiction but is one that must come from the government (cabinet). The Adjusted Budget that complemented the MTBPS reflects the key points in Godongwana’s speech as highlighted below:

The Ten Largest Adjustments: October 2021

Job Creation

A total allocation of R13 billion was earmarked in the 2021 budget speech for future allocations that will primarily address job creation initiatives. Allocations were made to various departments to assist them in their capacity to create jobs. For instance, the department of Higher Education and Training received R190 million from the Presidential Youth Employment Intervention, wherein R90 million is allocated for hiring graduate assistants. The Department of Trade, Industry and Competition received R800 million in future allocation also from the Presidential Youth Employment Intervention to support social economic activities in communities. Furthermore, R6.47 billion has been earmarked in the National Treasury department to allocate to the Provincial equitable share to build human resource capacity in key social sectors- basic education, health and social development respectively. R6 billion is allocated for the Basic Education employment initiative, R120 million for the appointment of social workers, and R350 million for staff and assistant nurses as part of the presidential youth employment intervention.

Social Interventions

The strength of South Africa’s economic recovery relies on a workforce that has their basic needs met such as access to quality healthcare, food, water and education. The Minister stressed that economic reconstruction will have limited success if the country cannot sustain the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination programme. So far, only 22% of South Africa’s population has been fully vaccinated, therefore R2.342 billion has been allocated to ensure continued purchasing and rollout of vaccines. Concerning social support for the unemployed population, R26.2 billion is allocated to the Department of Social Development to fund the reinstatement of the special R350 COVID‐19 social relief of distress grant until 31 March 2022.

Other key budgetary interventions to redress social needs included a R210 million roll-over to the school infrastructure backlogs grant. The Eastern Cape province received most of the grant amount (R132 million) in order to replace unsafe school structures and schools made entirely of inappropriate structures; and to provide water, safe sanitation and electricity at schools where these are lacking. Finally, an additional R81.3 million was allocated to the Department of Water and Sanitation, specifically to the Regional Bulk Infrastructure Grant to develop, refurbish, upgrade and replace ageing bulk water and sanitation infrastructure of regional significance. This grant is for the George local municipality to implement the potable water security and remedial works project.

Stabilising the Debt Crisis and ‘Tough love’ to State-Owned Entities

Increasing spending in key social areas requires sustainable funding but the growing cost of South Africa’s debt service costs has, according to the National Treasury, become a major risk to spending in critical areas. Borrowing cost is now higher than pre-pandemic levels and in the next three years, debt-service costs will on average consume 21 cents of every rand collected in main budget revenue. Higher interests and currency depreciation will further reduce space to spend on essential public services over the next three years as R423.4 billion of debt borrowed in previous years matures. The Minister’s proposal is to narrow the budget deficit, in other words, ensuring that government revenue is higher than expenditure. A big task ahead considering total expenditure on the social wage is now at R1.1 trillion. This proposal requires managing the potential trade-offs associated with economic restructuring. This will be achieved by offering no concessional funding to state-owned entities.

State owned entities such as power utility Eskom continue to drain the fiscus. A special dispensation has been approved to allow Eskom to access additional guaranteed debt of R42 billion in 2021/22 and R25 billion in 2022/23, which falls within its existing guarantee facility. Beyond this, however, the power utility will not receive any additional funding. Denel – state-owned military technology supplier is facing difficulties in meeting its obligations as several repayment obligations have fallen due this year. Government has allocated R2.9 billion in 2021/22 to settle these repayments.

The transparency of public finances at all levels of government is in the interests of all South Africans. Public scrutiny of public budgets and related fiscal policy decisions is a vital way of tracking alignment between policy objectives and financing. More importantly – ensuring greater transparency and participation in the budget process is a safeguard of democratic space as it bolters accountability in the use of public resources. In years to come -we hope to see a deepening of public participation within fiscal policy in South Africa – particularly in the pre-budget and formulation phases.

How to Budget for Covid-19 Response?

Hélène Barroy, Ding Wang, Claudia Pescetto, and Joseph Kutzin (WHO)

25 March 2020

**The original, full version of this article appears via WHO: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/health-financing/how-to-budget-for-covid-19-english.pdf?sfvrsn=356a8077_1

The COVID-19 pandemic requires sufficient public funding to ensure a comprehensive response. Reprioritizing public spending toward bolstering the economy and the health system requires timely action from government leaders and a supportive public finance environment. Highly-affected countries have taken various approaches to budgetary allocation, depending on their public financial management (PFM) and regulatory systems. Adjustments are required on the revenue side of budgets (e.g. loans) to account for these new economic and fiscal constraints. Quick decision making on the expenditure side is also needed. That will be the focus of this blog. Every country must develop specific processes for allocating budget funds to the response. To inform budgetary response in countries where the pandemic may spread in the near future, a summary of observed budgetary practices in some highly-affected countries, is provided below, with the aim of informing other countries about responses to three key questions:

— What are the immediate spending actions that can be taken with existing budgets?

— How to secure budget for COVID-19 response through revisions in finance laws?

— What can be done to accelerate budget execution and funds release to the frontlines?

1. Using existing budgetary flexibility and exceptional spending procedures to fund first measures

PFM systems, in most affected countries, provide some level of flexibility for the executive branch to use budgeted allocations. Reprioritization through virements between line items or within budgetary program envelopes (subject to thresholds) is a first permitted action to secure budget funding for immediate COVID-19 response. Further, most legal frameworks provide for activation of contingency funds by the executive in emergency situations. For instance, the declaration of a national emergency by the President allows the US administration to utilize the Stafford Act, a federal law governing disaster-relief efforts, making US$50 billion in emergency funding available to states and territories. Similarly, in China, the budget adjustment procedure for emergency situations defined in the 2018 budget law was used to allow for budget reallocations and the activation of contingency funds and reserves.

In several countries, the senior-most members of the executive such as the head of state or the finance minister can also take emergency regulations to authorize urgent spending for an immediate response within existing budgets and through simplified approval mechanisms. China’s Ministry of Finance issued a budget notice on 31 January 2020 serving as budgetary regulations for budget holders, sub-national entities and purchasers to ensure prompt budget funding for the prevention and control of COVID-19. Similarly, the heads of state or finance ministers in several European countries (e.g. France, Germany, Italy) used decrees to free-up budgetary resources for service providers. Governments of lower-income countries have moved quickly to reduce recurrent, non-priority spending and to reprioritize public spending toward responding to the crisis. The Finance Minister of Indonesia said on 18 March 2020 that the government would halt non-urgent spending and reallocate up to US$650 million from the state budget for COVID-19 relief.

State budget flexibility allows many countries to increase budget transfers to sub-national levels and purchasers. In most countries affected by the pandemic, sub-national levels (e.g. provincial governments in China) and/or purchasing agencies (e.g. national health insurance funds in Korea and Japan) have delegated authority for healthcare spending. Under normal conditions, these levels receive budget transfers approved within the state budget or through a separate budgetary development and approval process (e.g. a separate finance law for the national health insurance fund in France). China increased central budget transfers to Hubei, the province at the centre of the outbreak, at the height of the crisis to 6.2 billion RMB for prevention and control of COVID-19 (as of 05 March 2020). France adopted an ad hoc budget increase of 2 billion euros for the national health insurance fund to pay for masks and tests.

2. Accelerating revision of finance laws to secure a budget for the response through expenditure earmarking

Existing flexibility in the use of budget resources may facilitate urgent spending. However, the scale of the resources needed for the response often require supplementary budgets. The budget enactment process secures funding through expenditure earmarking. In several countries, the legislature enacted spending plans for the response (e.g. Korea, France, Germany, Japan, US, UK). Countries have developed rapid costs estimates and identified low-priority spending, which is preferable to across-the-board cuts. That said, some countries have opted for such measures, with reductions of 15–30% of the operating budgets of ministries not related to the response. Some legislatures have adopted their spending bills using curtailed processes allowed in such emergencies, many with all-party support, (submitted 18 March 2020 by French PM and adopted 19 March by national assembly and 20 March 2020 by senate), and with health precautions taken for their votes.

While several executive decisions have been made in the US over the past two weeks, on March 18, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act was signed into law with bipartisan support from Congress. As of March 25, the Presidential administration and Congress reached agreement toward passing an unprecedented relief package of US$ 2 trillion. In parallel, at least twelve states have enacted legislation that either appropriates additional funding for the COVID-19 response or authorizes a transfer of funds from the states’ rainy day funds In a context of closing legislatures, the adoption process has been curtailed, too. For example, in Canada:

“Estimates usually involve a detailed discussion of spending numbers in a week’s worth of committee meetings, but (this) procedure was limited to a three-hour debate in the chamber. The government made sweeping changes to speed up proceedings that stretched late into the night. If we do not pass this budget expeditiously we will not have the certainty that come April 1, the first day of the new fiscal year, that we will have the funds required to pay our doctors and nurses in this time of crisis.”

-Premier Jason Kenney in the Alberta Legislative Assembly, March 17 2020

From a budget formulation and structure perspective, supporting documents should be as robust as possible. Supplementary bills from the US, France, or Germany include costs estimates, explanations of cuts and re-allocations, a description of the planned activities, which is essential for executing and tracking expenditures. For instance, France’s proposal for its revised finance law is a 44-page document and includes four main parts: a report on the economic and budgetary situation and justification for modifications; a detailed presentation of modifications; an analysis by program of the changes; and a performance framework. When countries formulate budgets by budgetary programs, it allows them to group supplementary expenditures for the pandemic into a budgetary envelope earmarked for the response. France is earmarking through the creation of a specific budgetary programme dedicated to the response (i.e. “Emergency plan for health crisis”), with two sub-programs each with a related action. Similarly, in the first budget under the new government in the UK, provisions include supplementary programme lines for the National Health Service (£5 billion), provided that other changes in the public budget will be presented in the autumn budget 2020. Countries that present budgets by line items may need to create a temporary lump sum/programme-type line in supplementary budgets to secure funding and facilitate execution process for the response.

In some other highly affected countries, the spending plan continues to be implemented through the executive branch using exceptional procedures without enacting a new budget. Chinese leaders managed their response through a series of MoF “Notices” (31 January 2020 and 4 March 2020) at the central level since the lockdown in Wuhan, addressed to budget centres, sub-national levels, insurance funds and service providers. The central government adopted a rigid earmarking process to ring-fence COVID funds. The MoF notice issued on 31 January 2020 explicitly mentions that earmarked transfers to sub-levels should only be used for the response and forbid fungibility:

“Before, during, and after the event, standardize the procedures for approving funds, and ensure that funds are earmarked for special use. It is strictly forbidden to use financial subsidy funds for overstandard renovation or purchase of equipment, equipment, and transportation that are not related to epidemic prevention and control”.

Australia, whose new budget was due mid-May, decided to delay the submission of the 2020-2021 budget to October due to the uncertainties in crafting a budget in this context. In the meantime, the government introduced a “supply bill”, a precautionary measure used in an emergency to ensure financial supply when appropriation bills are not passed in the usual timeframe.

3. Releasing public funds to frontline service providers timely and facilitating expenditure tracking

It is essential for countries to explore ways to ensure public resources are made available to the frontlines through timely and effective budget execution processes. Throughout the crisis, China has provided flexibility in execution rules. In a 31 January 2020 budget notice addressed to subnational entities and purchasers, the finance ministry indicated:

“Local financial departments should accelerate the disbursement process, allow advance appropriation and fast-track payment to meet the spending needs. The local financial departments at all levels should strengthen the analysis and judgment of the situation of the treasury funds, orderly and standardize the organization of fund dispatch, and if necessary, take measures such as advance allocation and advance payment to prioritize the allocation of funds for epidemic prevention and control”.

While flexibility is provided in the use of resources, control procedures are typically adjusted to accelerate disbursement. France has adopted a fast-track expenditure authorization procedure, where a step in the spending authorization procedure has been removed to accelerate the release of funds. In the revised law, full amounts are automatically released for expenditure authorization and are equal to appropriations. Put another way, the ability to spend is facilitated and accelerated. Other priority disbursement procedures can be adopted by governments within supplementary budgets to accelerate the availability of funds and/or allow quick purchasing through a simplified procurement process. For instance, cash advances have been implemented in China, where advance payments have been made by insurance funds to health facilities to lessen the financial pressure on Hubei province. As of 19 February, insurance funds had disbursed more than 17 billion RMB to health facilities. Australia also provided swift supplementary allocations at the federal level, earmarking funds for primary health networks to set-up respiratory clinics. Countries can also use ex-post and/or risk-based controls (e.g. focus controls on high costs such as large purchases or infrastructure upgrades that are more susceptible to fraud), especially in cash-based management settings.

While accelerating the release of funds and softening spending procedures, countries should act to secure reporting and accountability mechanisms in the use of resources for the response. Several countries have started to define performance frameworks. France’s new budgetary programs are accompanied by clearly defined policy goals and performance indicators and targets. In the same vein, China strengthened reporting and supervision capacities at the provincial level. To secure accurate reporting, IFIMS or any alternative system used to monitor public spending needs to be updated to reflect changes in budget lines and allow a consolidated reporting of COVID-19 expenditures. Program envelopes can facilitate expenditure tracking and secure accountability in resource use, if all expenditures for the pandemic are to be reported under the same program code.

While multi-actor spending is often needed, typically finance authorities take a lead role in the financial accountability of the response. New spending plans are generally under the finance minister’s or the prime minister’s authority, as in China, Germany and France. The new budgetary programme in France is under the budget ministry, while spending can be executed by various 5 ministries and entities and accounted for under the budgetary mission code reported by budget ministry.

In conclusion, as the pandemic starts spreading through lower-income countries and in fragile contexts where PFM systems already suffer from systemic weaknesses, learning from higher-income countries about how to budget for the response is essential. Ensuring an appropriate balance between flexibility and accountability is relevant now more than ever under these exceptional circumstances. Governments and legislature need to ensure sufficient budgetary funds, by reprogramming existing spending and earmarking additional funds. Funds need to be made available rapidly to the frontlines, while setting effective expenditure tracking mechanisms to guarantee the effective use of resources and accountability. Finally, it is recommended to countries to engage as early as possible in the budgetary process to secure rapid response from domestic sources, while they also streamline external sources toward that goal.

We acknowledge inputs received from Tomas Roubal (WHO Western Pacific Regional Office), Tsolmongerel Tsilaajav (WHO South East Regional Office), and Agnès Soucat (WHO Headquarters).

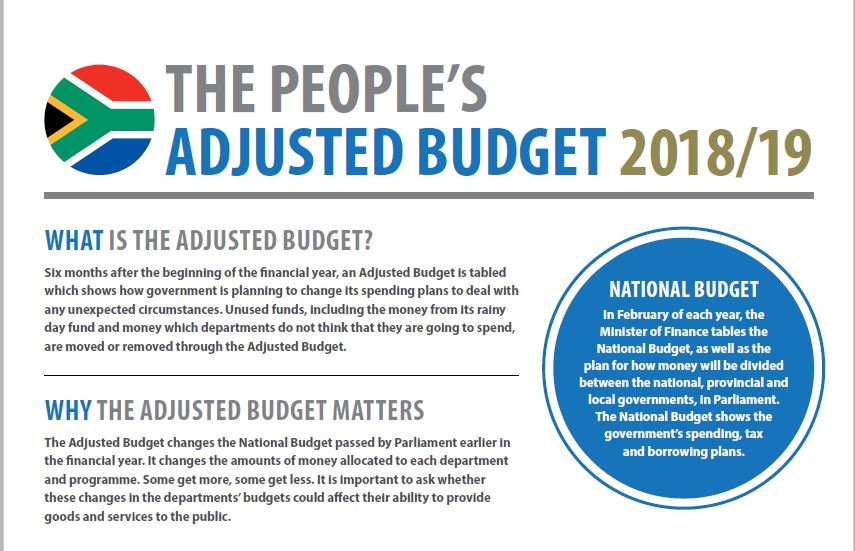

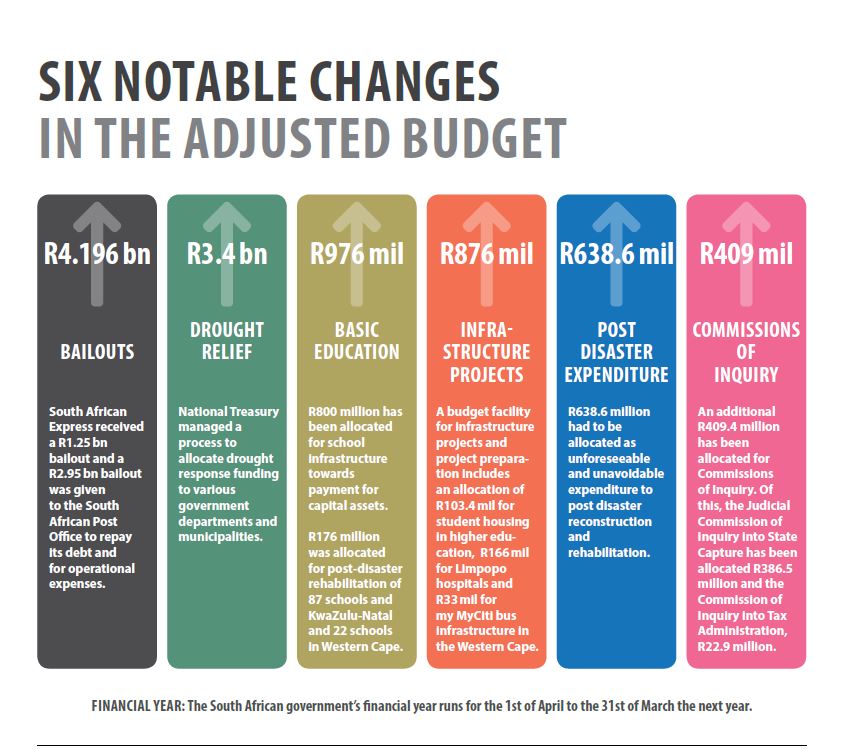

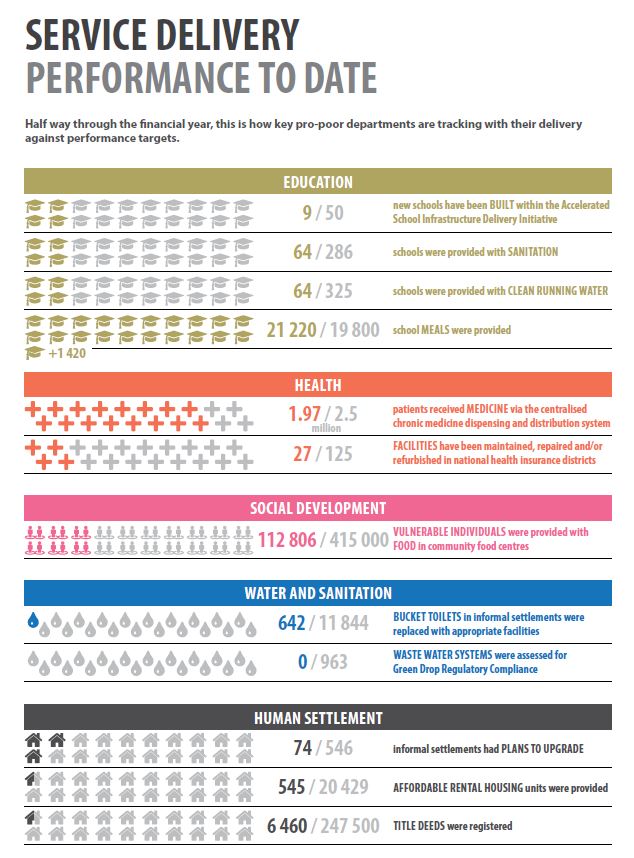

A Guide to the 2018 Adjusted Budget and Medium Term Budget Policy Statement

30 November 2018

Section 12 of the Money Bills Amendment Procedures and Related Matters Act obliges the Minister of Finance to table a Division of Revenue Amendment Bill alongside the revised fiscal framework with budget adjustments to the Division of Revenue Act and an Adjustment Appropriations Bill.

Further to this – Sections 30 (2)(B) and 31(2)(b) of the Public Finance Management Act also outlines specific roles and responsibilities for provincial Members of the Executive Councils (MECs). This includes the requirement for provincial treasuries to table an adjustments budget within 30 days of the tabling of the national adjustments budget where a national adjustments budget allocates funds to a province. Accounting Officers are also obliged to motivate accordingly for adjusted budgets.

This period within the fiscal calendar therefore constitutes an important opportunity for members of the public and civil society organisations to participate in the budget process. Civic actors and members of the public can participate in the Medium Term Budget Policy Statement (MTBPS) and Adjustments Budget primarily by participating in parliamentary public hearings scheduled after the MTBPS

So why is the People’s Guide to the AENE an important resource?

The work of IMALI YETHU, the Public Service Accountability Monitor (PSAM) and members of the Budget Justice Coalition to broaden, deepen and support public participation seeks to complement progress being made in relation to fiscal transparency in South Africa.

Access to credible information is central to meaningful participation. By simplifying budget data our – objective is to better support budget advocacy and provoke debate. Distilling and summarizing vast amounts of budget information also allows us to highlight areas of concern such as underspending, overspending or inefficient expenditure.

This has also fostered meaningful, direct engagement with public officials and government departments.

Below are extracts from the 2018/19 People’s Guide to the Adjusted Budget which is also available on Vulekamali: https://vulekamali.gov.za/datasets/contributed/people-s-guide-to-the-adjusted-budget-2018-19

Deriving an Open Data Ecosystem for the VulekaMali Open Budget Portal of South Africa

By Prof Caroline Khene (MobiSAM, Dept Of Information Systems, Rhodes University)

September 2018

The Open data movement has become a key focus for a number of countries globally, as it potentially stands as a key tool in building government accountability and transparency, civic participation, and innovation in decision-making in the public and private sector . The development and launch of the VulekaMali Open Budget portal is certainly a strategic move by National Treasury to support citizen engagement and accountability measures for government expenditure and performance. I have been involved in the consultation process as part of the Imali Yethu Coalition on Open Budgets, from the inception of the project, to its current continuous development. My experience in the process, observing the great opportunities the portal provides, and also the realistic challenges of adoption, implementation and uptake, lead to my question – Does South Africa have the right context to effectively harness such a significant tool for accountability?

When one thinks of context, the circumstances that form a setting are considered. The context of South Africa is complex in relation to the social, economic, political and cultural factors that drive decisions made at an individual, community or national level. In the development and implementation of stages of the VulekaMali Open Budget Portal, these circumstances need to be considered in relation to how various stakeholders from different walks of life participate in the development and use of the open budget data, or the lack thereof of this participation. National Treasury’s mandate is that the portal is user friendly to the citizens of South Africa – but one has to ask, is this realistically achievable. Several studies indicate that open government data failures stem from factors that emanate from a supply-driven approach to implementation associated with a lack of sufficient attention to the user perspective. National Treasury and the service provider implementing the portal, OpenUp, have attempted to address this by conducting community information drives in each province of South Africa, incorporating Data Quests and Hackathons to elicit the true needs of citizens in making the portal useful to them. This has proven successful in some aspects, however, effective participation in the CIDs can sometimes be limited due limited attendance, motivation and interest, and an understanding of the role that citizens or government participants play in the portal’s development, use and evolution. The approach for developing VulekaMali has been an engaged process with government and civil-society, hence moving away from a traditional supply-driven approach to open data, where government only decides on what or how data will be accessed. However, a clear structure or ecosystem needs to be clearly defined, which illustrates the cycles of feedback between data providers, data users, and data beneficiaries, as well as open government data and advocacy processes. This ecosystem provides a guide for National Treasury, OpenUp, Imali Yethu and other citizen and government participants to understand the aspects that need support (including how they can be supported), in order to realise the true benefits of the VulekaMali open budget portal in the South African context.

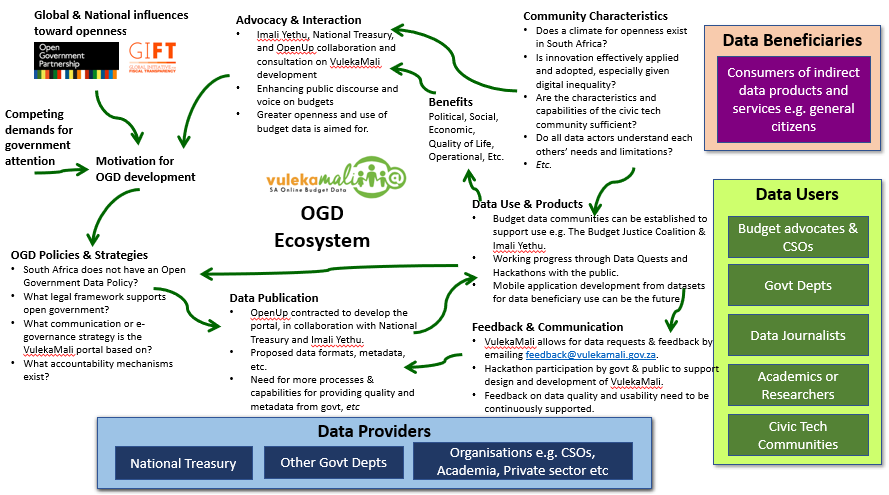

A research article by Dawes et al. (2016) on “Planning and Designing Open Government Data Programs: An Ecosystem Approach”, presents an insightful structure for an Open Government Data ecosystem. This ecosystem illustrates the various processes and interactions between data providers, data users, and data beneficiaries. The model is a good guideline to build and define the evolving ecosystem of the VulekaMali open budget portal, identifying keys areas that are addressed in its current operation, and areas that still need to be addressed in its evolving development and use. I provide an abstract view in Figure 1, adapted from Dawes et al. (2016) and based on my observations thus far – fully acknowledging that clearly defining a VulekaMali ecosystem in the South African context would require an in-depth longitudinal study (my future publication focus).

Figure 1: A Preliminary Illustration of the VulekaMali OGD Ecosystem

Actors in the VulekaMali ODG Ecosystem

The key actors of almost any OGD ecosystem include data providers, data users, and data beneficiaries:

- Data Providers: In the VulekaMali portal, these mainly refer to government departments at National and Provincial level. Local government data is mainly available via the Municipal Money portal – although there have been calls to provide a direct link between National, Provincial and Local government level data for effective civic engagement around issues that affect citizens at an individual and/or community level locally. VulekaMali also uniquely allows CSOs and other organisations or individuals to provide data, based on their own analysis of primary data provided by government. This allows data users to build on this analysis, and compare various datasets that confirm or explain government budgeting on various aspects.

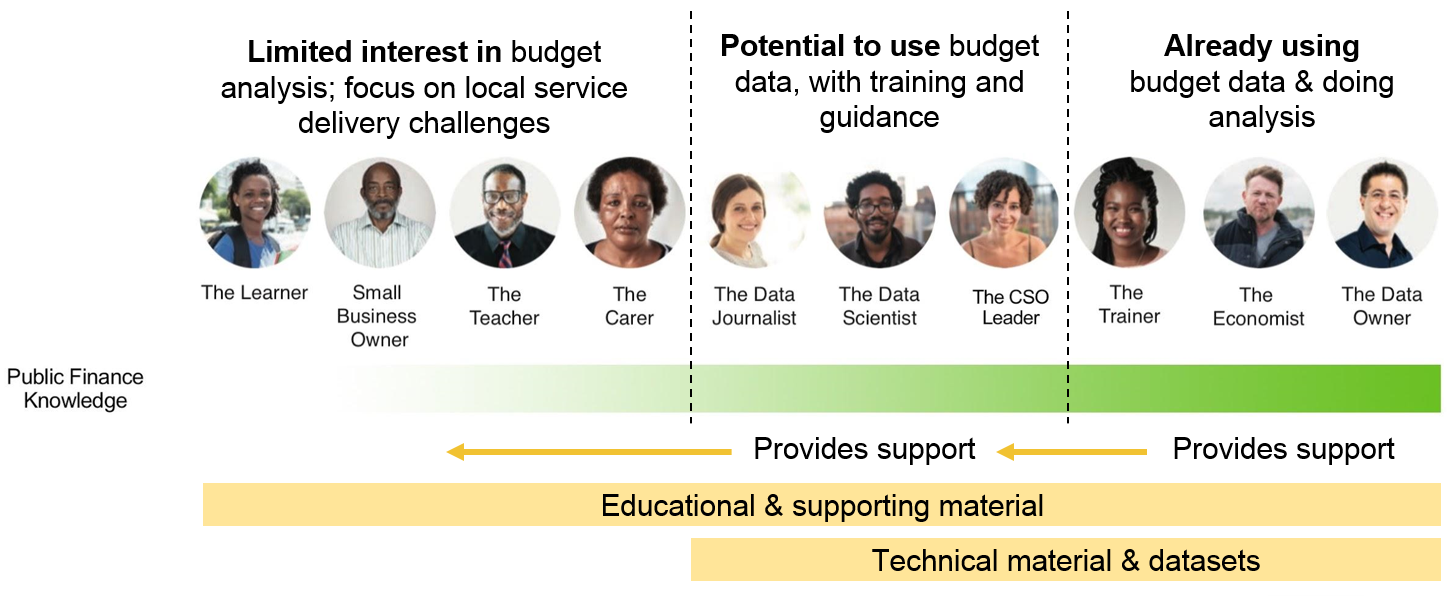

- Data Users: These are actors who can directly access and use datasets or data analysis on the VulekaMali portal. Realistically, this does not apply to every citizen in South Africa, as one needs to have sufficient domain knowledge and budget literacy, as well as the technical skill to access, explore and analyse datasets made available. Based on the community information drives that have been held in the Western Cape, Gauteng, and Mpumalanga provinces in South Africa, OpenUp has identified key user personas that represent the various categories of citizens that seek value from government information, but have varying skill sets to do so. Figure 2 illustrates the different user personas based on their public finance knowledge, with the left colour gradient showing limited public finance knowledge, and the right towards more skilled personas with significant public finance knowledge.

-

Data Beneficiaries: this group consists of

individuals, organisations, or communities that benefit

indirectly from products and services that emanate from data

analysis conducted on on datasets accessed on the VulekaMali

portal. This data analysis is usually conducted by data

users, who share the results of their analysis via

publications, reports, media articles, and even via mobile

applications that provide easily understandable summaries of

a particular budget aspect. Support for data beneficiaries

is still a working progress in VulekaMali’s development –

nonetheless, this category of actors at local level, are the

main voices that should be heard and promoted as they

experience the most challenging aspects of service

delivery.

Figure 2: User Personas and varying Public Finance Knowledge

The Context of the VulekaMali ODG Ecosystem

The interactions and engagement with all key actors of the OGD ecosystem provide the context which true benefits can be realised from the VulekaMali open budget portal. Furthermore, this context highlights key challenges that are still experienced in South Africa, and can influence the effective use and adoption of the portal. However, identifying these challenges does not indicate the portal will be unsuccessful, but rather highlights aspects that need to be mitigated and addressed overtime, as the ecosystem evolves. As illustrated in Figure 1, the VulekaMali OGD ecosystem is non-linear in nature, requiring multiple interactions back and forth between the elements in the context, as they each influence the successful functioning of the ecosystem. This is illustrated by the arrows in Figure 1. Therefore, most of the elements in the OGD context are interconnected, and a clear understanding of how this is the case, is a step in the right direction in mitigating or addressing some constraints faced in the development, use, and adoption of the VulekaMali open budget portal. Furthermore, it also provides an idea of opportunities to promote open data use and adoption in various innovative spaces.

Promoting citizen participation in fiscal matters: Towards a citizen participation guide or handbook?

By Yeukai Mukorombindo, 7 May 2018

The IMF Fiscal Transparency Handbook and the OECD Budget Transparency Toolkit were launched on the 23rd of April 2018 at the 2018 World Bank Group Spring Meetings in Washington DC. The Fiscal Transparency Handbook provides detailed guidance and describes current trends in implementation of fiscal transparency principles, noting relevant international standards as well outlining select country examples. The Budget Transparency Toolkit provides practical steps for how governments can support openness, integrity and accountability in public financial management. The launch of these handbooks is timely and very pertinent, particularly for Southern Africa. The Open Budget Index (OBI) is the world’s only independent, comparative measure of central government budget transparency. The last OBI 2017 survey reveals a decline in open budget survey scores in Sub Saharan Africa. Not only were governments in Southern Africa ranked poorly for making budget information publicly available and accessible but they were also ranked poorly in terms of providing public participation opportunities “both to inform decisions about how government raises and allocates funds and to hold government accountable for implementing those decisions.” The Open Budget Survey’s participation measure assesses the opportunities governments are providing to civil society and the public. Accessing relevant information on public resource management as well as finding opportunities to engage government in the formulation of the national budget is therefore a significant challenge in the Southern Africa context. The OBI 2017 survey highlights the need for civic actors in Southern Africa to advocate for greater accessibility on information pertaining to public finance management as well as the provision of meaningful opportunities for the public to engage in decisions about how public resources are raised and spent. Although the launch of handbooks setting standards for fiscal transparency is to be praised and is a step in the right direction, standards and guidelines on fiscal transparency are meaningless and empty if they are not accompanied with citizen participation in fiscal processes.

Why citizen participation in fiscal processes matters

Civic engagement is being increasingly viewed as a promising approach to improving development. Citizens’ involvement in public policy processes and their participation in the use of public funds is believed to be an effective empowerment tool also contributing towards good governance and improved public sector performance. In recent years, a growing number of authors and practitioners have offered civic engagement as the solution to the crisis of failed service delivery. It is believed that citizen voice and the involvement of ordinary citizens in the formulation, monitoring and implementation of public resources can address service delivery shortcomings such as dilapidated school buildings, clinics with no electricity or medication, absent teachers and nurses, the lack of water or electricity and the like. Citizen participation is understood as having potential to improve government responsiveness and influencing decisions over spending and policy.

The concept of social accountability draws from a participatory democracy premise which acknowledges that elections will always be insufficient a mechanism for citizen voice and accountability. It also implies the right for citizens to hold elected representatives accountable for their performance and their right to directly participate in decision making in policy and governance. Participation by citizens in public policy and decision-making are fundamental principles of democracy. However it must be pointed out that although citizen participation is potentially a powerful accountability tool, it is often quite dormant and apathetic. It is therefore important to design mechanisms and set standards that help to translate the potential power of citizen participation into action and results.

Barriers to citizen participation in fiscal matters

Leading thinkers such as John Dewey made the case for direct citizen participation by arguing that “citizens are highly capable of understanding complex scientific and technical information.” The excuse that most governments give for not providing citizens with opportunities to participate in fiscal matters is that citizens are not capable of engaging with financial information and policies. Whilst this may be true to an extent, the lack of capacity (which can be overcome) is only a part of the problem. There are other contributing factors that exist within the context preventing citizens from participating.

Challenges such as economic inequality and the absence of interest can hamper participation by citizens. This therefore means that the capacity for citizens to engage in participatory governance can be constrained by a lack of economic resources, access to information and low levels of education among citizens and civil society organisations (CSOs). Citizen’s interest in participation depends on the perceived costs and benefits of participation. Costs could include time and transportation costs. The costs could also include the perceived risk of challenging public officials weighed against possible benefits such as the transfer of real decision making power over public resources and improved access to public services.

The capacity of citizens to participate effectively in fiscal matters is further weakened by financial information relayed in formats that are inaccessible and not understandable to the average citizen. This often requires translation of documents into indigenous languages as well as the use of visual techniques. However, most governments lack the capacity and resource costs to implement such practices which impacts on the quality and sustainability of the participatory processes.

Standards for meaningful citizen participation

An important component of evaluating citizen participation in fiscal matters is an assessment of the citizen participation opportunities and experiences during the budget formulation process. Remember being consulted and informed about what the government plans to do with public resources is not a favour, it is a right! Participation opportunities become tick box exercises if they are not meaningful. Not only do citizens require opportunities to participate in fiscal processes, they also require that these opportunities be meaningful. Some guidelines on key features of effective, meaningful and inclusive participation or deliberation is provided by the Institute for Development Studies (IDS). The IDS argues that in order for participation to be meaningful, it must meet the following standards:

- Careful consideration, debate and discussion of reasons for and against.

- Active involvement of multiple social actors and usually emphasises the participation of previously excluded citizens.

- Social interaction in the form of face-to-face meetings between those involved.

- Multiple positions are given equal opportunity and respect.

- Discussion and presentation of positions and perspectives is based on information and evidence.

- Negotiations, public reasoning and dialogue aimed at mutual understanding takes place, even if consensus is not being sought.

- Unhurried, reflective and reasonably open-ended discussion is required.

- Citizens have accurate and accessible information on resource allocation, performance and service delivery

Conclusion

The benefits of fiscal transparency are dependent on citizen’s willingness and ability to attend participate in fiscal processes. In order to maintain public interest in participation meetings, simply organising opportunities for participation is not enough. Citizens must see a link between their input in public meetings and what happens on the ground. Furthermore, to maintain public interest and engagement in participation initiatives there must be meaningful engagement. This will require that international financial institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, the OECD also work towards building standards and capacities for developing citizen participation practices in fiscal matters. The lack of meaningful citizen participation in fiscal matters can undermine as well as weaken attempts to promote transparency and accountability in the use of public resources.

IMPROVING PARTICIPATION IN THE BUDGET PROCESS – by Kirsten Pearson

Shortly prior to the 2018 Budget Speech, it was announced that South Africa achieved joint first place with New Zealand in the Open Budget Index 2017 survey. This is an impressive achievement that South Africa can be proud of. The Open Budget Index is the world’s only independent, comparative measure of central government budget transparency. Each country is given a score between 0 and 100 that determines its ranking. South achieved 89 out of 100 for transparency, whereas the global average is 43 out of 100.

South Africa’s Open Budget Index scores

South Africa is a top performer globally, having consistently ranked in the top four and above in the Open Budget Index rankings since the survey was initiated. But, what can South Africa do to maintain its ranking and to improve outcomes for citizens? On the measure of public participation, South Africa scored 24 out of 100. This is an area that the International Budget Partnership which undertakes the Open Budget Index Survey has identified as an area for improvement for South Africa.

Recommendations for Improving Participation in the Budget

Process

The International Budget Partnership has

identified three main actions that South Africa should

prioritize to improve public participation in its budget

process:

1. Pilot mechanisms for members of the public

and executive branch officials to exchange views on national

budget matters during the monitoring of the national budget’s

implementation. These

mechanisms could build on

innovations, such as participatory budgeting and social

audits.

2. Hold legislative hearings on the formulation

of the annual budget, during which any members of the public

or civil society organizations can testify.

3. Establish

formal mechanisms for the public to assist the supreme audit

institution in formulating its audit program and to

participate in relevant audit investigations.

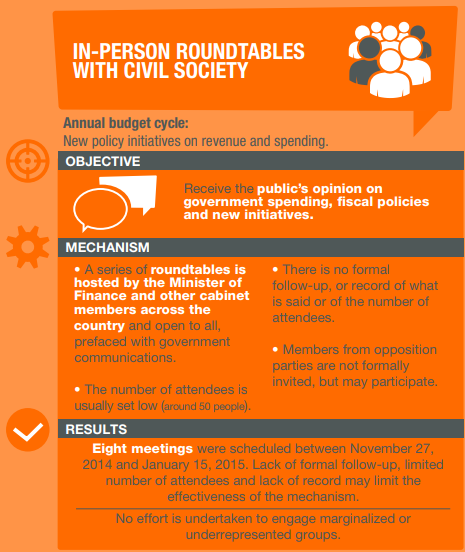

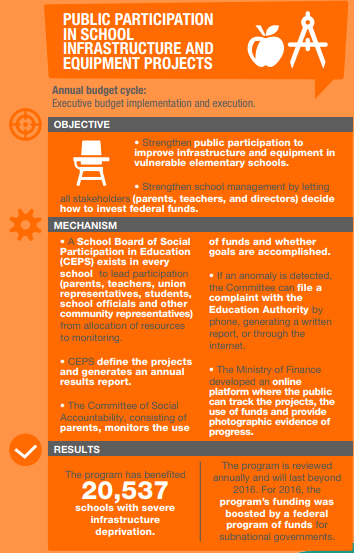

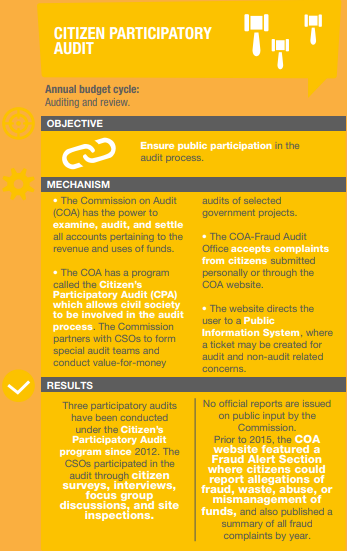

The Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency has compiled an informative series of country case studies, which profile the mechanisms that a variety of countries have used to improve participation. See: fiscaltransparency.net/mechanisms. Four of these mechanisms for improving participation are selected and profiled below as possible inspiration for South Africa, based on the International Budget Partnership’s prioritized recommendations.

PARTICIPATORY BUDGETING

Actions South Africa could take: In order to receive the public’s opinion on priorities for government spending and the fiscal framework, the Minister of Finance could undertake to hold a series of in-person roundtables with civil society. Certain of these roundtable engagements could be themed in accordance with sectoral interests that CSOs express or priority issues for the country. Additional cabinet members could be included based on their portfolios.

Next steps: IMALI YETHU and National Treasury to prepare a

memo to the Minister of Finance suggesting roundtables with

civil society.

Source:

GIFT

PARTICIPATORY BUDGETING

![]()

Actions South Africa could take: There is an urgent need to address poor infrastructure in South African schools, including the provision of safe bathroom facilities. IMALI YETHU, the Department of Performance Monitoring and Evaluation and the National Treasury could create an online platform to monitor the implementation. The International Budget Partnership has outlined what data is needed to do adequate monitoring. The platform can allow for photographic evidence to be submitted by communities. In the longer term, the broader approach that Mexico has taken can be considered.

Next steps:

– IMALI YETHU, DPME and National

Treasury to prepare a concept note for a monitoring platform

or the incorporation thereof into an existing platform.

–

Joint approach to the Department of Basic Education offering

to partner to ensure success.

PUBLIC HEARINGS ON THE FORMULATION OF THE ANNUAL BUDGET

![]()

Actions South Africa could take: To initiate public

hearings at Parliament that form part of pre-budget

consultations, IMALI YETHU and National Treasury could

approach Parliament to request consideration of this proposal.

Next steps:

– Develop a draft submission to

Parliament.

– Circulate draft submission to CSOs,

NGOs and academics for inputs.

– Submit to

Parliament.

– Engage with Parliament regarding

submission.

MECHANISMS FOR THE PUBLIC TO ASSIST THE AUDITOR GENERAL

![]()

Actions South Africa could take: To ensure public participation in the audit process, IMALI YETHU could approach the Auditor General to partner in a Citizen Participatory Audit process, which would allow CSOs to provide support in the audit process. GTAC conducts Performance Expenditure Reviews (PERs). It could be proposed to the Auditor General’s office that part of a pre-audit engagement process would be to receive presentations on PERs. There is also an opportunity to set up formal partnerships to combat corruption.

Next steps:

– Develop a letter to the Auditor

General regarding Citizen Participatory Audits and pre-audit

engagements on the efficiency of spending.

– Engage

with the Auditor General’s Office to develop a partnership

between whistleblower organisations and the AG’s office.

Source:

GIFT

Important new report on participatory budgeting & its impact on service delivery & community trust:

Participatory Budgeting (PB) is spreading quickly and now exists in environments that are very different from Porto Alegre, Brazil, where it began, including places as diverse as New York City, Northern Mexico, and rural Kenya. It is increasingly used as a policy tool and not as a radical democratic effort, which was its original purpose. PB also now exists at all levels of government around the world, including neighborhoods, cities, districts, counties, states, and national governments, although it is most widely implemented in districts and cities. Many donors and international organizations support PB efforts, as do non-profit advocacy organizations in countries that use PB.

PB is rapidly expanding across the world because many of its core tenets appeal to many different audiences. Leftist activists and politicians support PB because they hope that PB will help broaden the confines of representative democracy, mobilize followers, and achieve greater social justice. PB is also attractive within major international agencies, like the World Bank, European Union, and USAID, because of its emphasis on citizen empowerment through participation, improved governance, and better accountability.

Governments, donors, and activists hope that PB will produce social change on different levels. First, it is hoped that PB will produce attitudinal and behavioral change at the individual-level, including among citizen participants, elected officials, and civil servants. PB advocates hope that PB programs will induce broader support for democratic policy-making processes, help build social trust, and build greater legitimacy for democracy. Second, PB advocates hope that PB will have spill-over effects that produce broader changes in four general areas, listed below.

– Stronger civil society: PB creates a stronger civil

society by increasing CSO density (number of groups),

expanding the range of CSO activities, and promoting new

partnerships with governments.

– Improved

Transparency: PB improves transparency by generating greater

citizen and CSO knowledge, allowing for more oversight and

monitoring, and increasing the efficiency of budget

allocations.

– Greater accountability: PB improves

governance and accountability because citizens are more likely

to be aware of their rights and government activity through

PB. Government officials will then respond to citizens’

demands and collaborate in pursuit of shared interests.

–

Improved Social Outcomes: PB improves social outcomes through

improved governance, newly-empowered, better-informed

citizens, as well as through the allocation of public-works

projects that focus on the needs of underserved communities.

This report, written in 2018, is published at a time of dynamic change in the PB field. We acknowledge that there are books, and articles with important insights that we were unable to include in this synthesis. It is our hope that this report will aid citizens, governments, practitioners, and donors as they contemplate how PB programs may improve the quality of democracy, service delivery, community trust, and well-being. We thank David Sasaki, the Hewlett Foundation, and the Omidyar Network for their support throughout the process of developing this report.

Full report accessible at: HERE

Zukiswa Kota

On 31 January 2018, the news that South Africa had been ranked number one on the Open Budget Index (OBI) offered welcome respite from the heavy news of recent months. A little celebratory jig was certainly in order and I imagine this was the case in the hallways of the National Treasury – even briefly.

The Open Budget Survey (on which the OBI is based) draws on internationally accepted criteria across 109 indicators to measure budget transparency. Amongst others, these indicators are used to determine whether the national government makes eight key budget documents available to the public in a timely manner. The indicators also assess the usefulness and comprehensiveness of the data in these documents. The OBI is a composite ranking of each country out of a possible score of 100. According to the International Budget Partnership (2015) – the OBS is “the world’s only independent and comparative measure of budget transparency.” In 2017 the survey looked at 115 countries.

While this transparency score is a veritable achievement for all advocates of open government and fiscal transparency in South Africa – the ultimate objective remains somewhat elusive. The OBI also measures the degree to which the government creates opportunities for the public to engage in budget processes throughout the fiscal calendar. Importantly – this also includes engagements with supreme audit institutions (the Auditor-General) as well as the legislative and the executive sectors. Here the news is dismal. Scoring 24 out of 100, South Africa is not the worst in the world but is certainly not a shining example of public participation in budgeting.

It is commonly acknowledged that transparency is not an end in itself but it constitutes a vital step towards achieving the goals of greater accountability and improved public resource governance. As proponents of both fiscal transparency and public participation – one of IMALI YETHU’s missions is to ensure that we progressively go #beyondtransparency. Thus the emphasis on inclusive, participatory processes.

There are several interesting examples of public participation or participatory budgeting around the world. Kenya and Mexico are noteworthy. The Kenyan Constitution enacted in 2013 makes some provisions for citizen participation within its devolved budget process. This means citizens are afforded opportunities at the county level to have their voices heard on fiscal issues affecting them. While elements of participatory budgeting can be identified in the Mexican context as early as the 1980s, the enactment of the Citizen Participation Law of the Federal District in 2010 introduced greater state investment in participatory budgeting processes at the local government level. This law stipulates, for instance, that 3% of each local authorities’ budget must be spent on participatory budgeting activities. In both these countries – there are clear benefits of participatory budgeting but the authors of a 2018 study by mySociety that explores these in greater depth – highlight the importance of interrogating the objectives, methodologies and outcomes of these processes. The knowledge that these processes are inherently political, interest-driven and complex should inform the design of participatory budgeting interventions – digital or otherwise.

The Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency (GIFT) recently devised new principles on public participation which include accessibility, respect for self-expression, inclusiveness and timeliness across the various stages of the fiscal policy cycle. It is these principles that were used to inform the questions pertaining to public participation in the 2017 OBS. These ten principles are now globally accepted norms on public participation in national budget processes and constitute an important strengthening of the OBI indicators.

GIFT’s Lead Technical Advisor, Murray Petrie, reflecting on lessons from the OBS public participation results raises the following points that are helpful reminders for civil society and government reformers alike;

“If more governments do not become more inclusive in how they design and implement taxation and public spending, we are much less likely to counter the negative trends with respect to inequality, willingness to pay taxes, and trust in government. One challenge from OBS 2017 is to work much harder on inclusive public engagement in the management of public finances.…..direct public engagement has the potential to transform the disclosure of fiscal information into more effective accountability and better development outcomes.”

And – here is comes a particular gem of a reminder about the value of a platform such as vulekamali;

“….the ICT revolution has given it a major shot in the arm, by dramatically cutting the cost of direct interactions between governments and citizens, as well as by making possible entirely new forms of public participation.”

It is these new ways of thinking, engaging and doing that we must collectively embrace. As with any quest – the unknowns, unknowables and risks are abundant. Along the way there will be naysayers and detractors but ultimately the commitment to achieving something outrageously ambitious must sustain us. In this case – the team working on vulekamali have the outrageously ambitious goal of going #beyondtransparency towards participatory budgeting and a system in which accountable governance and effective, inclusive service delivery is a reality.

Let’s embark on this quest to travel #beyondtransparency – join us!

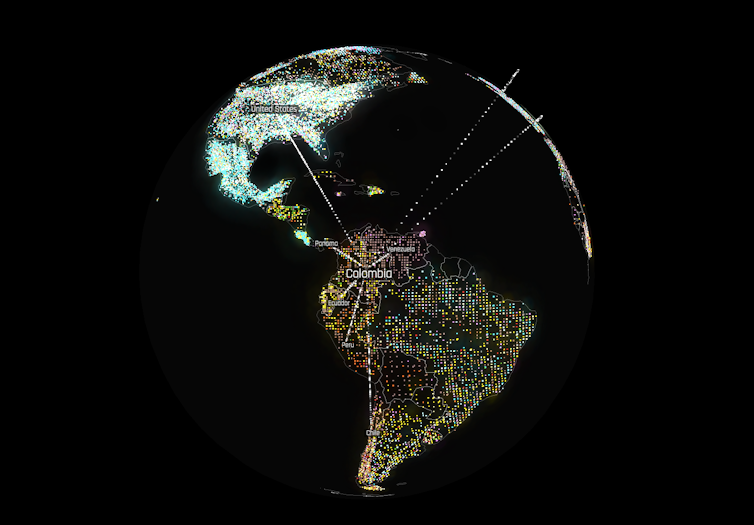

How open data can help the Global South, from disaster relief to voter turnout

CID, Harvard University, CC BY-SA

Stefaan G. Verhulst, New York University

The modern era is marked by growing faith in the power of data. “Big data”, “open data”, and “evidence-based decision-making” have become buzzwords, touted as solutions to the world’s most complex and persistent problems, from corruption and famine to the refugee crisis.

While perhaps most pronounced in higher income countries, this trend is now emerging globally. In Africa, Latin America, Asia and beyond, hopes are high that access to data can help developing economies by increasing transparency, fostering sustainable development, building climate resiliency and the like.

This is an exciting prospect, but can opening up data actually make a difference in people’s lives?

Getting data-driven about data

The GovLab at New York University spent the last year trying to answer that question.

In partnership with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the non-profit FHI 360 and the World Wide Web Foundation, we scoured the evidence about what roles open data, particularly government data, can play in developing countries.

The results of our 12 in-depth case studies from around the world are now out. The report Open Data in Developing Economies: Toward Building an Evidence Base on What Works and How offers a hard look at the results of open data projects from the developing world.

Our conclusion: the enthusiasm is justified – as long as it’s tempered with a good measure of realism, too. Here are our six major takeaways:

1. We need a framework – Overall, there is still little evidence to substantiate the enthusiastic claims that open data can foment sustainable development and transform governance. That’s not surprising given the early stage of most open data initiatives.

It may be early for impact evaluation, but it’s not too soon to develop a model that will eventually allow us to assess the impact of opening up data over time.

To that end, the GovLab has created an evidence-based framework that aims to better capture the role of open data in developing countries. The Open Data Logic Framework below focuses on various points in the open data value cycle, from data supply to demand, use and impact.

The GovLab

2. Open data has real promise – Based on this framework and the underlying evidence that fed into it, we can guardedly conclude that open data does in fact spur development – but only under certain conditions and within the right supporting ecosystem.

One well-known success took place after Nepal’s 2015 earthquake when open data helped NGOs map important landmarks such as health facilities and road networks, among other uses.

And in Colombia, the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture launched Aclímate Colombia, a tool that gives smallholder farmers data-driven insight into planting strategies that makes them more resilient to climate change.

Beyond these genuinely transformative experiences, we found several examples that ran into challenges.

A pair of education-information dashboards in Tanzania, for example, were launched with good intentions (to improve student test scores by empowering families with information on school quality). But lacking long-term strategies to scale and sustain their use and impact, these efforts soon fizzled out.

3. Open data can improve people’s lives Examining projects in a number of sectors critical to development, including health, humanitarian aid, agriculture, poverty alleviation, energy and education, we found four main ways that data can have an impact.

Open data can improve governance, as it did in Burundi when the country made public its results-based financing system. By linking development aid to pre-determined target results, this information increased transparency and accountability.

Data can also empower citizens by enabling more informed decision-making. For example, by providing information on voter registration centres, Kenya’s GotToVote! system increased voter awareness – and, consequently, turnout.

By enabling economic growth and innovation, data also has the power to create opportunities. In Ghana, the Esoko platform is helping smallholder farmers maximise the value of their crops by providing useful information about increasingly complex global food chains.

Finally, data can assist governments, NGOs, and citizens in solving major problems. Dengue has been endemic since 2009 in Paraguay. Recently, open data helped researchers develop a new tool for predicting outbreaks of the disease.

4. Data can be an asset in development While these impacts are apparent in both developed and developing countries, we believe that open data can have a particularly powerful role in developing economies.

Where data is scarce, as it often is in poorer countries, open data can lead to an inherently more equitable and democratic distribution of information and knowledge. This, in turn, may activate a wider range of expertise to address complex problems; it’s what we in the field call “open innovation”.

This quality can allow resource-starved developing economies to access and leverage the best minds around.

And because trust in government is quite low in many developing economies, the transparency bred of releasing data can have after-effects that go well beyond the immediate impact of the data itself.

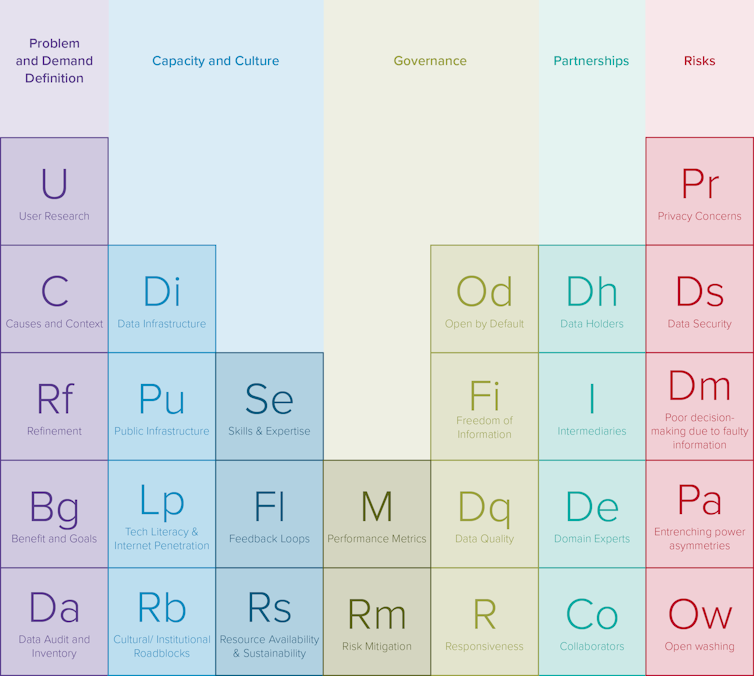

The GovLab, Author provided

5. The ingredients matter To better understand why some open data projects fail while others succeed, we created a “periodic table” of open data (below), which includes 27 enabling factors divided into five broad categories.

The GovLab

For those who can truly unlock the potential of open data – from practitioners to policy-makers – this table could serve as a checklist of the factors and ingredients to be considered and addressed. Researchers assessing the impact of an open data project can also use it to determine what variables made a difference.

6. We can plan for impact Our report ends by identifying how development organisations can catalyse the release and use of open data to make a difference on the ground.

Recommendations include:

· Define the problem, understand the user, and be aware of local conditions;

· Focus on readiness, responsiveness and change management;

· Nurture an open data ecosystem through collaboration and partnerships;

· Have a risk mitigation strategy;

· Secure resources and focus on sustainability; and

· Build a strong evidence base and support more research.

Next steps

In short, while it may still be too early to fully capture open data’s as-of-yet muted impact on developing economies, there are certainly reasons for optimism.

Much like blockchain, drones and other much-hyped technical advances, it’s time to start substantiating the excitement over open data with real, hard evidence.

The next step is to get systematic, using the kind of analytical framework we present here to gain comparative and actionable insight into if, when and how open data works. Only by getting data-driven about open data can we help it live up to its potential.

![]() This article was co-authored by

Andrew Young, Knowledge Director at the GovLab.

This article was co-authored by

Andrew Young, Knowledge Director at the GovLab.

Stefaan G. Verhulst, Co-Founder and Chief Research and Development Officer of the Governance Laboratory, New York University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

It’s a pity you don’t have a donate button! I’d most certainly donate to this fantastic blog! I guess for now i’ll settle for book-marking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to brand new updates and will talk about this blog with my Facebook group. Chat soon!

harrisburg seo experts

Hi there, Richardmig – just a reminder to please also keep an eye out for updates on

https://vulekamali.gov.za/events – and perhaps see you at one of the upcoming events if you’re in South Africa!